Bay Journal

Tom Horton | Jun 17, 2024

Turns out Virginia can be as irresponsible as Maryland in managing the Chesapeake Bay.

Eight years ago marked a low point in Bay fisheries management as the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, in the sway of Republican Gov. Larry Hogan, fought to avoid doing a critical study to see whether oysters were being overfished. You cannot manage species — DNR’s legal mandate — if you don’t know how many are there, any more than you can manage your money if you don’t know how much you have.

By April of 2016 it had been around 130 years since scientists made a good cut at counting oysters. DNR didn’t want to count because oystermen didn’t want it to. Everyone knew there was a good chance it would point to some overfishing.

Ultimately, legislation requiring an oyster “stock assessment” passed the Democratic General Assembly. It turned out there was overfishing, but not everywhere; and I’d argue that eight years later Maryland’s oystermen are doing okay and have forged working relationships with scientists and environmental groups.

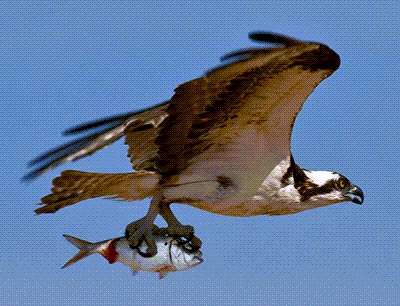

Now, move south to Virginia, and shift from oysters to menhaden, an oily little fish that filters plankton from the water. It translates plant life into flesh for predators higher in the food web, from migrating loons and nesting ospreys to striped bass.

“All fish in the Bay are just menhaden in other form,” wrote William K. Brooks,

a Johns Hopkins scientist in the 1800s, extolling the abundance and importance of Brevoortia tyrannus.

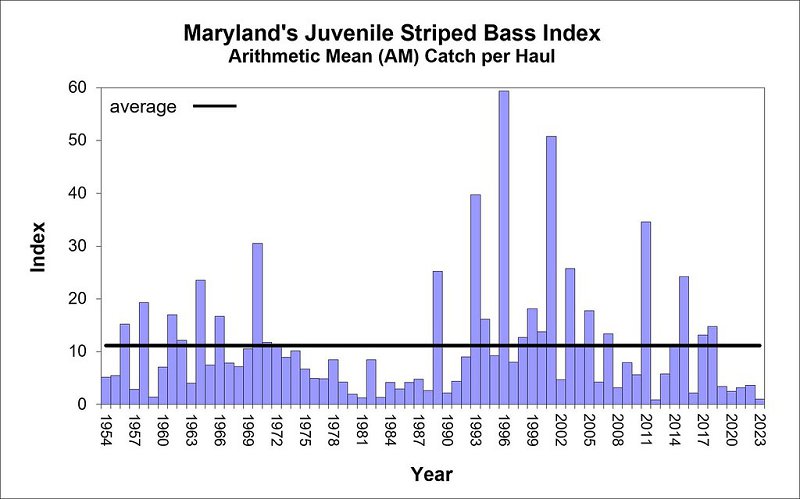

Striped bass are in trouble these days, not reproducing well, prompting controversial new catch limits on anglers for whom they are fine eating and great sport, and who themselves are the economic lifeblood of the charter boat industry.

Throughout Maryland and Virginia there is a hue and cry, and legal actions, all insisting the problem is overfishing of that very important striped bass chow, the menhaden.

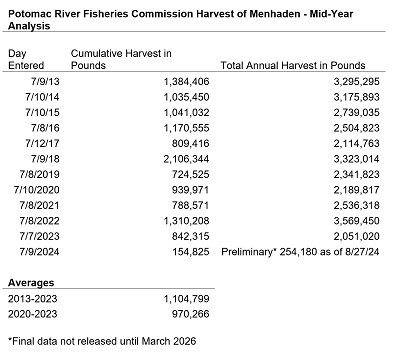

An inviting culprit for the overfishing is Canadian-owned Omega Protein in Reedville, VA, whose fleet of oceangoing vessels, aided by spotter aircraft, catches menhaden by the hundreds of millions of pounds annually. Employing “purse seines,” nets that encircle massive menhaden schools, their boats fish the Virginia Chesapeake and along the ocean coasts to supply the Reedville plant. Maryland bans such fishing.

Omega pulverizes menhaden into animal food products, oils and, to a lesser extent, the company says, feed for the farmed salmon of its Canadian parent company, Cooke, Inc.

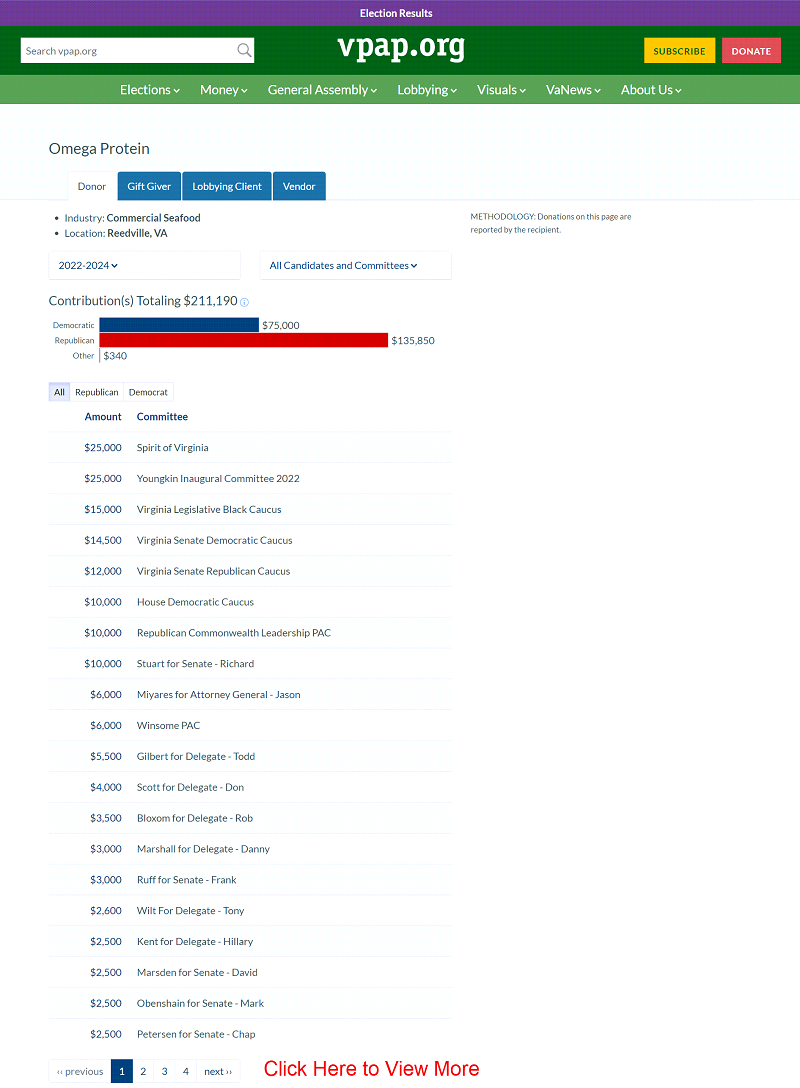

The solution may seem obvious: Restrict politically powerful Omega, which has given $215,000 to Virginia legislators in the last three years.

But it is not obvious, because Virginia has never done the science to understand menhaden abundance in the Chesapeake, just as Maryland had not with oysters.

“They could be overfished,” says Rob Latour, a leading fisheries ecologist with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. “But the fact is we don’t know.”

Some complicating factors emerged from my conversation with Latour — factors that striped bass advocates sometimes overlook.

Menhaden as a whole, meaning the Atlantic coastal population, are clearly healthy, even as menhaden in the Bay appear to be down.

Long-term VIMS studies are indicating that at least seven other once-common fish species, like spot, croaker and flounder, seem to be avoiding the Chesapeake in recent years, even though their overall numbers are healthy.

One possible explanation for lower menhaden numbers in the Bay — an extrapolation, actually, because the studies don’t involve menhaden — is warmer water, driven by climate change. When in the Bay, menhaden do gravitate toward the coolest portions.

And while menhaden are a very important food source for striped bass, perhaps even more important is a tiny species called the Bay anchovy, which is not harvested by humans and is abundant.

To remedy the knowledge gap, Latour and others — including Omega Protein, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and Maryland scientists — held a workshop in 2023. They emerged with a proposal for a three-year, $2.7 million study that, Latour says, “won’t put all concerns to rest, but would lead to an unparalleled advance in understanding what’s going on with menhaden in the Chesapeake.”

It was put forward in this year’s Virginia legislature as HB 19. Latour was particularly excited by a representative of Omega, who he said pledged that if the bill passed, the company would give scientists access to its private catch data, a treasure for anyone who wants a good “count” of menhaden.

But when the bill came up for its first test this winter, it was summarily dismissed by the House Rules Committee. According to Virginia newspaper reports, the only reason given by the committee's chairman, Democrat Luke Dorian of Prince William County, was: “I did what I was told to do.”

And so we remain awash in ignorance. For example, in April a petition from the nonprofit Chesapeake Legal Alliance to restrict menhaden fishing was denied by Virginia’s Marine Resources Commission with this pitiable statement: “We don’t know if [the current cap on menhaden harvests] should be significantly lowered, increased or exist at all.”

But the three-year study has to happen, says Latour, “or we’re stuck where we are.”

Ben Landry, a spokesman for Ocean Harvesters, which operates Omega’s fishing fleet, said Omega was officially neutral on HB 19 and denied rumors that the company killed it behind the scenes.

“We generally agree that there’s science that needs to be done on menhaden in the Chesapeake,” Landry said. But he declined to endorse the study, even while saying “we have enormous respect for Rob Latour,” who would lead it.

The bill will come up again in 2025, and here’s one thought: It could be very much in Maryland’s interest to go down to Richmond and offer to fund a study, to do the science if Virginia will not.